- Home

- Thorland, Donna

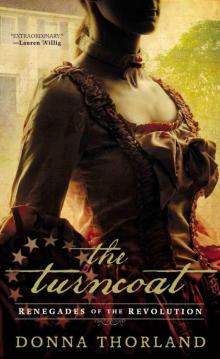

The Turncoat

The Turncoat Read online

the

Turncoat

RENEGADES OF THE REVOLUTION

DONNA THORLAND

NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

New American Library

Published by New American Library, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa), Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North 2193, South Africa

Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by New American Library, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Printing, March 2013

Copyright © Donna Thorland, 2013

Readers Guide copyright © Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Thorland, Donna.

The turncoat: renegades of the revolution / Donna Thorland.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-101-61506-5

1. Philadelphia (Pa.)—History—Revolution, 1775–1783—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3620.H766T87 2013

813’.6—dc23

Designed by Spring Hoteling

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

ALWAYS LEARNINGPEARSON

For my husband, Charles. Contra mundum.

One

The Jerseys, August 1777

Kate didn’t like Mrs. Ferrers. Something about the beautiful young widow was off. To exclude the newcomer on account of such vague feelings, however, would not be Quakerly, so Angela Ferrers, along with every other woman in Orchard Valley, was at Grey Farm that sweltering morning, packing supplies for the Continental Army.

“Yet Colonel Donop still refused to divulge the lady’s name at his court-martial,” Mrs. Ferrers said to her spellbound audience. “For all the good it did him. When the disgraced Hessian returned to find his lover—seeking vengeance, explanations, or further dalliance, who can say?—I’m told he discovered nothing but a cold hearth and an empty house.” The Widow folded back her fine cotton sleeve and reached for the pickle jar.

“Mrs. Ferrers, please don’t.” Kate tried for a note of polite deference and decided that polite frustration would have to do. “If you put your fingers in the jar, the brine will spoil.”

They were gathered in the kitchen, painted terra-cotta pink by Kate’s classically minded grandmother, around the pine worktable where she had learned to roll piecrust, pluck fowl, hull beans, and keep careful record of household stores.

Kate handed Mrs. Ferrers a ladle. The Widow cradled it like a royal scepter and went on with her story, the pickle jar entirely forgotten.

“But tell us, Mrs. Ferrers, about your late husband.” Mrs. Ashcroft was a dour Quaker matron of the old school, but today she sounded like a five-year-old asking for a bedtime story.

“Peter was a born Friend, like myself, and after our marriage we farmed his father’s land in Rhode Island,” Mrs. Ferrers began, “where we had, two years ago in the spring, the most extraordinary incident with a cow…”

The woman was an expert tale spinner, but she talked more than she worked.

Kate tried to be fair-minded. It was Mrs. Ferrers, rising from her bench beneath a rather convenient ray of sunlight during the Sunday meeting, who had convinced the congregation that Arthur Grey’s proposal to offer supplies did not contradict their Quaker pacifism. It was Mrs. Ferrers who argued that their goods would not prolong an already bloody war, but would save the lives of the men and boys starving in the Continental Army. Aiding the Rebels was an errand of mercy. The town drove cattle all the way to Boston when the British blockaded that city. They could certainly spare a few wagonloads of grain for men starving almost on their doorstep.

Angela Ferrers’ Quaker demeanor was pitch-perfect. She thee’d and thou’d when appropriate. She conformed to the Society of Friends’ preference for plain dress. She wore no lace, no gaudy colors, no frills, yet she stood out among the other ladies.

Her skirts were hemmed to show a tasteful, but well-turned, hint of ankle. Her bodice was expertly tailored. The beige cotton of her ensemble set off her hair and eyes. Peeking out from her collar, cuffs, and lacings were a chemise and stays of the most impeccable white. Even her teeth gleamed.

She fooled the other ladies because they wanted to be fooled, because they saw in her an ideal reflection of themselves. But she did not fool Kate.

The pickle jar was just the latest of her mistakes. Earlier that day she had stepped into the fireplace in the summer kitchen without hitching her skirts high enough. Only timely intervention from Kate had prevented the Widow’s skirts catching fire. Her pockets, though, clinched it. She didn’t have any: not a single one in her fitted skirts, jacket, or stays. The impracticality of it was astounding.

Kate left the women packing salt pork into the last of the barrels and debating the merits of linen versus cotton baby swaddling, and went to find her father at his secretary in the back parlor. It was dark and cool there, and she welcomed the relief from the sticky heat of the kitchen. She shut the door behind her.

It was her favorite room in the house, where she played the harpsichord in the evening and indulged her father’s un-Quakerly taste for ballads. Floored with Brussels carpet, painted in hues of sea blue and wheat gold, hung with classical scenes and furnished with a set of horsehair lolling chairs that bristled like angry porcupines, it served both as the Greys’ private sanctuary and their preferred place to entertain guests.

At sixty, Arthur Grey was still a vigorous man. The years had softened his hawklike features, but his eyes burned bright and his frame was lean.

“Are the wagons packed?” he asked.

“Almost. What will you do when Reverend Matthis discovers the contents of the last wagon?”

“What kind of an unmannerly oaf do you take me for, young woman? I will offer him one of your excellent pies, of course.”

“I meant the contents under the pies,” Kate persisted.

“That would be blueberries?” He turned from his secretary to cast a merry eye on his daughter.

“That would be rifles, sixty, with shot.”

“You disapprove.”

“I’m afraid for you.”

“Be afraid for the Regul

ars. I’m still a damned good shot.”

“You mean to stay with Washington, then.” She tried to hide her disappointment. Her father had been an officer in the French and Indian War; a man, at one time, of violence; and a close friend of the Virginian who now commanded the Continentals.

“These may be the times that try men’s souls, but our masters in London have tried my patience. I didn’t fight in the last war to put up with a standing army on my doorstep.” He pressed his seal into the wax pooled on the envelope. It bore no address.

“It’s your soul that Reverend Matthis will think the worse for wear. He’ll read you out of the meeting.”

“Would that be so terrible, Kate? I wasn’t born a Friend. I was convinced. Largely by your mother. She was a damned sight better-looking than Matthis, in any case.”

Kate laughed out loud. “I give up. Go and frustrate King George…How long will you be gone?”

He rose without answering and slid his hand along the mantelpiece, fingertips flying over courses of dentils, acanthus, frieze, and metope, to rest upon the stalk of an exquisitely carved pineapple. A tiny door swung open, revealing a cubby. He held up the letter. “For our friends in Philadelphia, by the next courier,” he said, and slipped the missive into its hiding place. When he closed the panel, between the acanthus-twined pilasters, the joint was invisible.

“Before you began writing treasonous letters to Rebels, what did you use that hidey-hole for?” Kate asked.

“Tobacco. Your mother hated me to smoke in the house. And it’s a Committee of Correspondence with like-minded gentlemen, not treason. Still, it wouldn’t do us any good to let the Regulars get hold of any of my letters, particularly that one. It’s important. I’m informing Congress that I will accept their commission and have tendered my advice on whom they might consider sending to Paris.”

“Mrs. Ferrers says that Howe has landed at Head of Elk and will begin arresting Rebels.” Everyone feared they would soon march on Philadelphia, de facto seat of the rebellion since the first Continental Congress had convened there three years ago.

“Then you’ll be safer with me away.” He handed her a heavy purse of golden guineas.

“What is this for?” she asked.

“Uncertainties.”

A suspicion formed in the pit of her stomach. “How long will you be gone?”

“That’s one of the uncertainties. I’m sorry, Kate.” He capped the inkpot, closed the doors of the secretary, and put his arm around his daughter.

“I’ll be lonely without you.”

“Then marry, Kate.”

“Never. ‘For I’ve been warned, and I’ve decided, to sleep alone, all of my life.’”

“Don’t put your faith in maudlin ballads. I seem to remember that one containing a philandering father.”

“A handsome devil of a philandering father.”

Arthur Grey grunted. “Well, they got that half right.” He paused, and something in his manner made Kate recall the time when she was a little girl and contracted a hoarse, bellowing cough. She had rebelled against taking the ichorous green tonic prescribed by the doctor, but every morning Arthur Grey had talked her into swallowing the draught.

“What?” she asked.

“I’ve asked Mrs. Ferrers to stay with you until Howe goes to ground for the winter.”

“No! I’m fine by myself. The Regulars know that Quakers are pacifists.”

“Tired, hungry soldiers don’t always trouble to pay for food, or firewood, or to discuss politics with the people they rob. Regulars or Continentals, for that matter. Mrs. Ferrers is staying.”

“She’ll drive me mad.”

“She is a sensible lady of great experience. Provided she doesn’t set herself on fire, you should have a quiet few weeks, and she’ll be gone by the first snow.”

* * *

By late afternoon, Kate was longing for snow.

The wagons departed in good order, though Silas Talbert, their neighbor to the south, returned an hour later when his horse went lame. This was generally perceived as the signal for the ladies to depart, though Kate found herself wishing that they had stayed later, both to occupy the chatty Mrs. Ferrers and to put the house to rights.

Kate spent the early afternoon scrubbing tables, sweeping floors, and taking count of their provisions. During these activities, Mrs. Ferrers was, not surprisingly, nowhere in sight.

They had sent away more than half their stores with the men. It would be a lean winter for Kate, Mrs. Ferrers, and Margaret and Sara, the two young girls who helped with the house and lived in the room above the winter kitchen.

Kate was in the cold room counting apples when the rider broke through the line of trees at the end of the barley field. She could see him from the second-story window, crossing straight over the meadow.

It was Silas Talbert again, but this time his horse was very definitely not lame. He was shouting. Kate lifted the sash and leaned out the window, wishing for a breeze to break this dizzying heat, and finally his words reached her.

“Regulars. Cavalry. Heading north. They’ll be on the house any minute.”

Kate stepped back from the window. Below she could hear Talbert riding away, his message delivered, his own family and farm to think of.

Her father’s words came back to her: it wouldn’t do the Greys any good if his letters fell into British hands. And no matter how he made light of them, those letters were treason.

Kate wasn’t certain if the distant thunder she heard was horsemen or the blood pounding in her ears. Hungry soldiers, who wouldn’t stop to ask their allegiance or talk politics. The thunder grew louder, and Kate looked back out the window. The road was hidden by a long stand of elms, but the sound of hooves carried over the field, and the branches shook with their passing.

She ran down the stairs and into the back parlor.

Kate expected an empty room and a cold grate. Instead, a woman stood at the fire, her back to the door, negligently feeding the contents of the secretary to the flames.

“Mrs. Ferrers?”

The woman turned. Gone was the plain young Quaker widow of the morning. In her place stood a powdered, perfumed, bewigged lady in silks and satins. Her dress was closely fitted, and the oyster pink satin shimmered in the firelight. Her wig was tinted the same soft pink, pale curls piled high on her head. She wore a diamond around her neck on a silky ribbon, and rings on her manicured hands.

Her cheeks were rouged, her skin powdered porcelain white, her eyes rimmed with kohl. The entire effect was stunning, particularly to a girl like Kate, raised in a community that eschewed such finery.

At a loss, she said, “There are men on the road. Cavalry. Regulars.”

“Yes. I know. A day earlier than I expected. Thirty men, I should say, in scarlet with buff facings, two pistols each, a carbine, and a saber. The man who leads them is tall, has fair hair that he does not allow to grow past his shoulders, blue eyes, and rather full lips.”

Stunned, Kate stepped farther into the room. “How do you know all this? They haven’t even reached the drive.”

As she spoke, the jingle of spurs came distantly from the road.

“Because,” said Mrs. Ferrers, closing the secretary and smoothing her spotless pink satin, “I’ve been waiting for him. Colonel Sir Bayard Caide commands a battalion of His Majesty’s horse in these, his Colonies, and has systemically murdered, robbed, and raped civilians in the execution of his duties. I have come, my dear child, to destroy him.

“Now,” Mrs. Ferrers went on coolly, “you are my niece. I am your dear aunt Angela from Philadelphia, staying with my dull Quaker cousins in the country. I will dazzle the colonel and persuade him to spend the night. You will see that a fit dinner is laid on for him and his officers. Is that clear?”

Kate found her voice with difficulty. “I’m not going to help you a kill a man. It’s not our way.” It sounded prim even to her own ears.

Mrs. Ferrers laughed, deep and throaty, a genuine sound, q

uite different from the hollow simper she had used in front of the ladies that morning. “My dear girl, I’m going to destroy him. You don’t have to kill a man to do that. Caide is a sybarite, a sadist, and above all things, a soldier. The cavalry is perhaps the only place where men like him can exist within the confines of the law. He thrives on violence with a bit of style. And what, after all, is an army in the field? I don’t need to kill him. I need only ruin him.”

She paused, abandoned her pose of elegant bravado, and spoke with chilling seriousness. “General Howe has landed at Head of Elk with eighteen thousand Regulars and Hessian mercenaries. He means to march on Philadelphia and take Congress and the capital. There will be arrests, hangings. Caide carries the plans for this attack, the routes, troop placements, and supply lists, from Howe to his subordinate General Clinton in New York. If I can relieve Caide of these dispatches, the colonel will be disgraced. At the very least, he’ll lose his commission. And in one move we can disarm a man who has caused us no end of trouble and gain an advantage over our enemy on the march—perhaps even have a chance to stop the British before they reach Philadelphia.”

“I can’t help you. I’ve sworn not to intervene in the conflict. We all have. You too…” Kate trailed off. “You’re not really a Quaker, are you?”

Mrs. Ferrers shook her head. “I’m sorry, Kate, but it was safer, until now, to keep this from you. I have known your father since the last war. I came here to convince him to join Washington. And I have remained to lie in wait for Bayard Caide.”

“But how did you know this…this…Caide man would come here?”

“Your house is the biggest estate in the county. It’s on the main road north. He was bound to stop here, but he’s too close on the heels of your father and the other gentlemen. Kate, you must help me. Your father will be traveling slowly. The wagons are heavy. If Caide doesn’t stop here tonight, he will overtake your father. Caide would give no quarter to Rebels carrying supplies for the Continentals.”

Kate could hear the men in the yard. Thirty mounted soldiers made a good deal of noise. She must think. She must decide. She must go out and speak to these men, and, it was becoming all too clear, she must lie.

The Turncoat

The Turncoat